Bill Mauldin Remembered

He

meant so much to

the millions of Americans who fought in World War II, and to those who

had

waited for them to come home. He was a kid cartoonist for Stars and

Stripes,

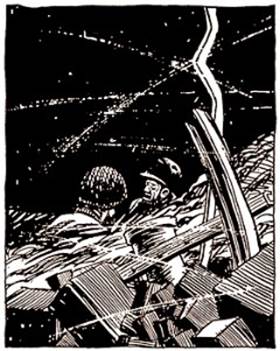

the military newspaper; Mauldin's drawings of his muddy, exhausted,

whisker-stubble infantrymen Willie and Joe were the voice of truth

about what

it was like on the front lines.

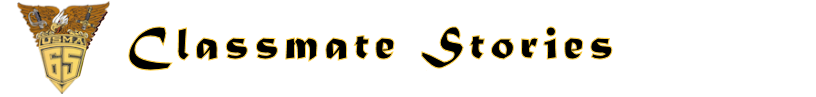

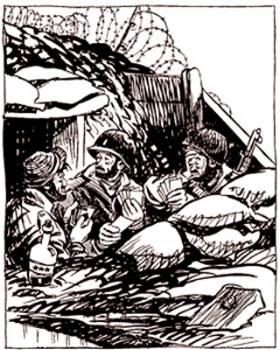

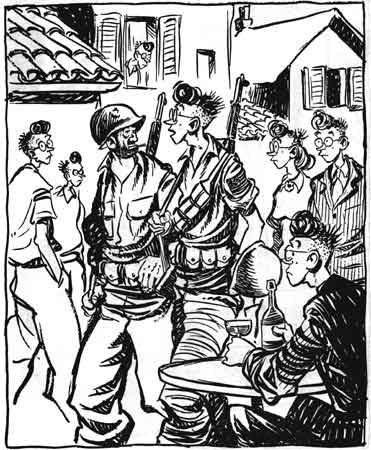

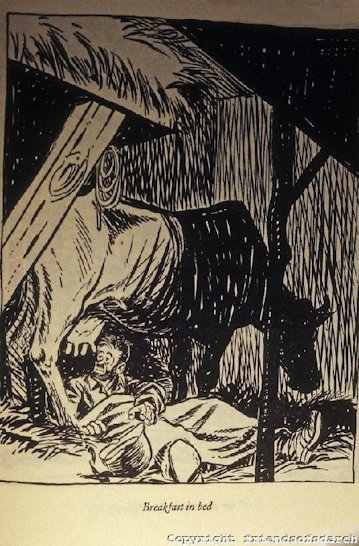

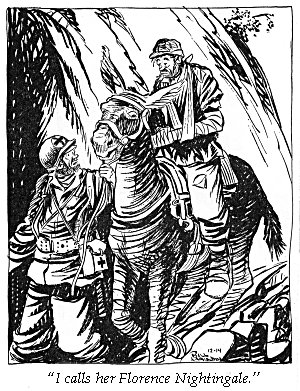

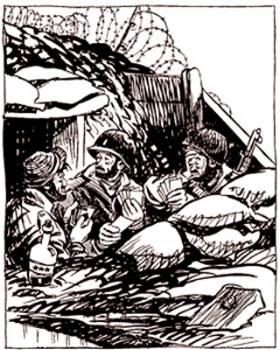

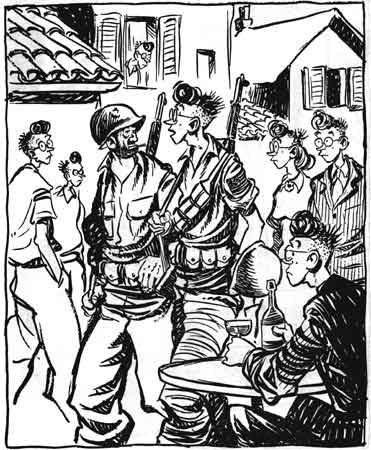

Mauldin was an enlisted man just like the soldiers for whom he drew; his gripes were their gripes, his laughs their laughs, his heartaches their heartaches. He was one of them. They loved him.

He never held back. Sometimes, when his cartoons cut too close for comfort, superior officers tried to tone him down. In one memorable incident, he enraged Gen. George S. Patton, who informed Mauldin he wanted the pointed cartoons celebrating the fighting men, lampooning the high-ranking officers to stop. Now!

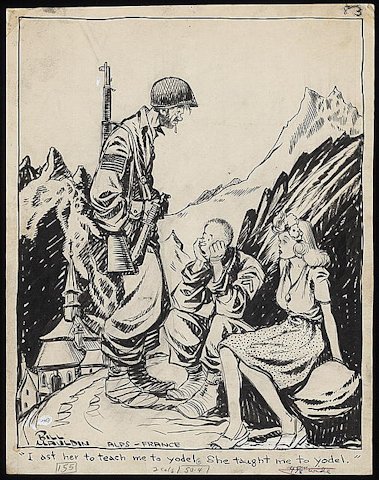

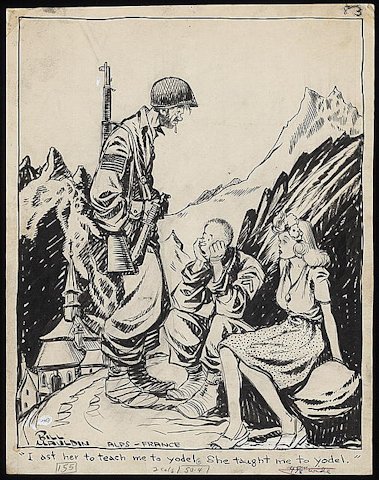

"I'm beginning to feel like a fugitive from the' law of averages."

The news passed from soldier to soldier. How was Sgt. Bill Mauldin going to stand up to Gen. Patton? It seemed impossible.

Not quite. Mauldin, it turned out, had an ardent fan: Five-star Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, SCAFE, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe . Ike put out the word: "Mauldin draws what Mauldin wants." Mauldin won. Patton lost.

If, in your line of work, you've ever considered yourself a young hotshot, or if you've ever known anyone who has felt that way about him or herself, the story of Mauldin's young manhood will humble you. Here is what, by the time he was 23 years old, Mauldin had accomplished:+

"By the way, wot wuz them changes you wuz

gonna make when you took over last month, sir?"

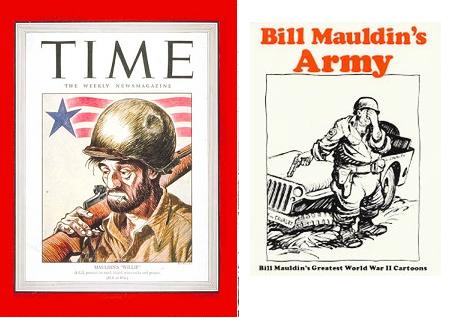

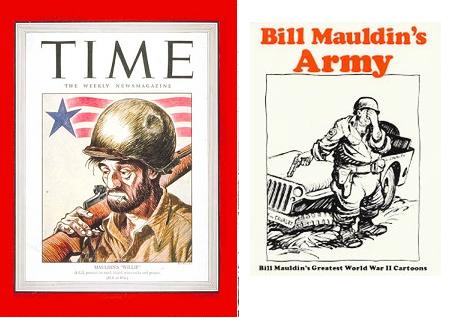

He won the Pulitzer Prize & was on the cover of Time magazine. His book "Up Front" was the No. 1 best-seller in the United States .

All of that at 23. Yet, when he returned to civilian life and grew older, he never lost that boyish Mauldin grin, never outgrew his excitement about doing his job, never big-shotted or high-hatted the people with whom he worked every day.

I was lucky enough to be one of them. Mauldin roamed the hallways of the I was lucky enough to be one of them. Mauldin roamed the hallways of the Chicago Sun-Times in the late 1960s and early 1970s with no more officiousness or air of haughtiness than if he was a copyboy. That impish look on his face remained.

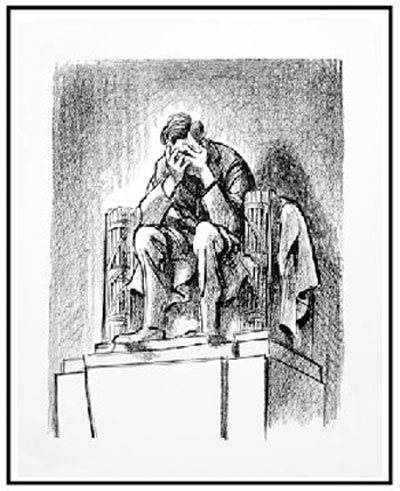

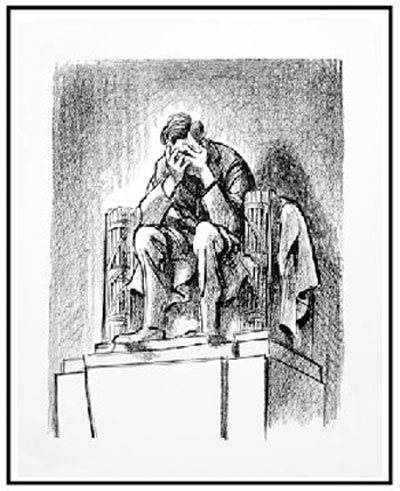

He had achieved so much. He won a second Pulitzer Prize, and he should have won a third for what may be the single greatest editorial cartoon in the history of the craft: his deadline rendering, on the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, of the statue at the Lincoln Memorial, slumped in grief, its head cradled in its hands. But he never acted as if he was better than the people he met. He was still Mauldin, the enlisted man.

During the late summer of 2002, as Mauldin lay in that California nursing home, some of the old World War II infantry guys caught wind of it. They didn't want Mauldin to go out that way. They thought he should know he was still their hero.

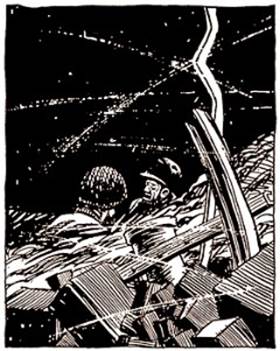

"This is the' town my pappy told me about."

Gordon Dillow, a columnist for the Orange County Register, put out the call in Southern California for people in the area to send their best wishes to Mauldin. I joined Dillow in the effort, helping to spread the appeal nationally, so Bill would not feel so alone. Soon, more than 10,000 cards and letters had arrived at Mauldin's bedside.

Better than that, old soldiers began to show up just to sit with Mauldin, to let him know that they were there for him, as he, so long ago, had been there for them. So many volunteered to visit Bill that there was a waiting list. Here is how Todd DePastino, in the first paragraph of his wonderful biography of Mauldin, described it:

"Almost every day in the summer and fall of 2002, they came to Park Superior nursing home in Newport Beach , California , to honor Army Sergeant, Technician Third Grade, Bill Mauldin. They came bearing relics of their youth: medals, insignia, photographs, and carefully folded newspaper clippings. Some wore old garrison caps. Others arrived resplendent in uniforms over a half century old. Almost all of them wept as they filed down the corridor like pilgrims fulfilling some long-neglected obligation."

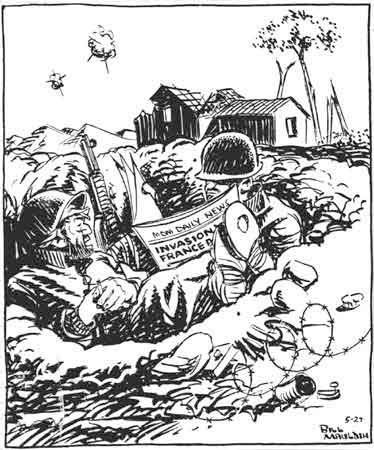

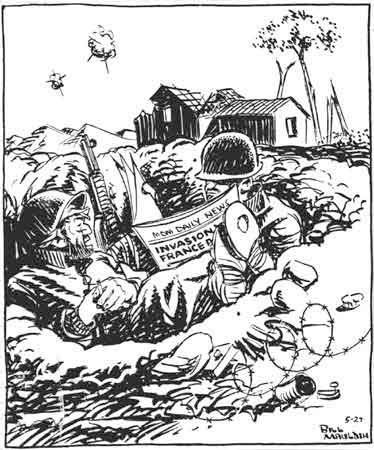

One of the veterans explained to me why it was so important: "You would have to be part of a combat infantry unit to appreciate what moments of relief Bill gave us. You had to be reading a soaking wet Stars and Stripes in a water-filled foxhole and then see one of his cartoons."

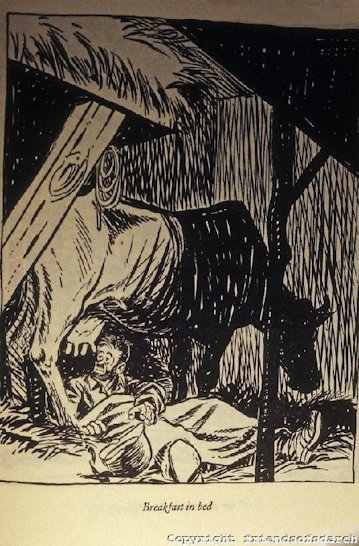

"Th' hell this ain't th' most important hole in the world. I'm in it."

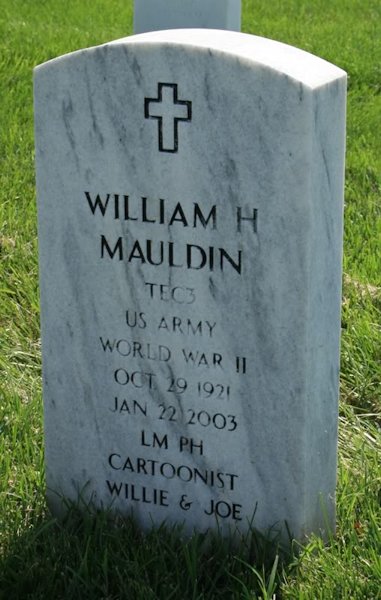

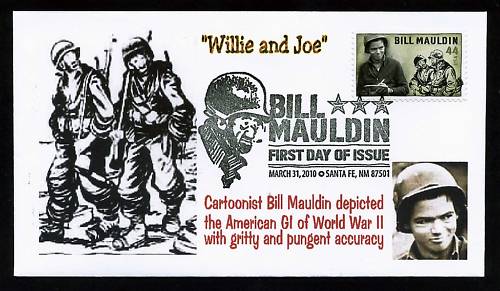

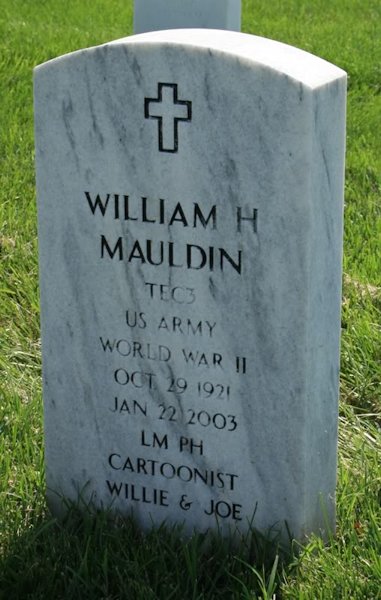

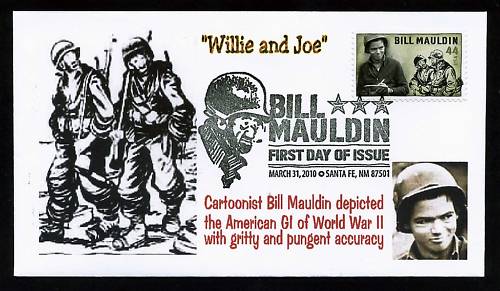

Mauldin is buried in Arlington National Cemetery . Last month, the kid cartoonist made it onto a first-class postage stamp. It's an honor that most generals and admirals never receive.

What Mauldin would have loved most, I believe, is the sight of the two guys who keep him company on that stamp.

Take a look at it.

There's Willie. There's Joe.

And there, to the side, drawing them and smiling that shy, quietly observant smile, is Mauldin himself. With his buddies, right where he belongs. Forever.

What a story, and a fitting tribute to a man and to a time that few of us can still remember. But I say to you youngsters, you must most seriously learn of, and remember with respect, the sufferings and sacrifices of your fathers, grandfathers and great grandfathers in times you cannot ever imagine today with all you have. But the only reason you are free to have it all is because of them.

I thought you would all enjoy reading and seeing this bit of American history!

Paul Schultz

Mauldin was an enlisted man just like the soldiers for whom he drew; his gripes were their gripes, his laughs their laughs, his heartaches their heartaches. He was one of them. They loved him.

He never held back. Sometimes, when his cartoons cut too close for comfort, superior officers tried to tone him down. In one memorable incident, he enraged Gen. George S. Patton, who informed Mauldin he wanted the pointed cartoons celebrating the fighting men, lampooning the high-ranking officers to stop. Now!

"I'm beginning to feel like a fugitive from the' law of averages."

The news passed from soldier to soldier. How was Sgt. Bill Mauldin going to stand up to Gen. Patton? It seemed impossible.

Not quite. Mauldin, it turned out, had an ardent fan: Five-star Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, SCAFE, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe . Ike put out the word: "Mauldin draws what Mauldin wants." Mauldin won. Patton lost.

If, in your line of work, you've ever considered yourself a young hotshot, or if you've ever known anyone who has felt that way about him or herself, the story of Mauldin's young manhood will humble you. Here is what, by the time he was 23 years old, Mauldin had accomplished:+

"By the way, wot wuz them changes you wuz

gonna make when you took over last month, sir?"

He won the Pulitzer Prize & was on the cover of Time magazine. His book "Up Front" was the No. 1 best-seller in the United States .

All of that at 23. Yet, when he returned to civilian life and grew older, he never lost that boyish Mauldin grin, never outgrew his excitement about doing his job, never big-shotted or high-hatted the people with whom he worked every day.

I was lucky enough to be one of them. Mauldin roamed the hallways of the I was lucky enough to be one of them. Mauldin roamed the hallways of the Chicago Sun-Times in the late 1960s and early 1970s with no more officiousness or air of haughtiness than if he was a copyboy. That impish look on his face remained.

He had achieved so much. He won a second Pulitzer Prize, and he should have won a third for what may be the single greatest editorial cartoon in the history of the craft: his deadline rendering, on the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, of the statue at the Lincoln Memorial, slumped in grief, its head cradled in its hands. But he never acted as if he was better than the people he met. He was still Mauldin, the enlisted man.

During the late summer of 2002, as Mauldin lay in that California nursing home, some of the old World War II infantry guys caught wind of it. They didn't want Mauldin to go out that way. They thought he should know he was still their hero.

"This is the' town my pappy told me about."

Gordon Dillow, a columnist for the Orange County Register, put out the call in Southern California for people in the area to send their best wishes to Mauldin. I joined Dillow in the effort, helping to spread the appeal nationally, so Bill would not feel so alone. Soon, more than 10,000 cards and letters had arrived at Mauldin's bedside.

Better than that, old soldiers began to show up just to sit with Mauldin, to let him know that they were there for him, as he, so long ago, had been there for them. So many volunteered to visit Bill that there was a waiting list. Here is how Todd DePastino, in the first paragraph of his wonderful biography of Mauldin, described it:

"Almost every day in the summer and fall of 2002, they came to Park Superior nursing home in Newport Beach , California , to honor Army Sergeant, Technician Third Grade, Bill Mauldin. They came bearing relics of their youth: medals, insignia, photographs, and carefully folded newspaper clippings. Some wore old garrison caps. Others arrived resplendent in uniforms over a half century old. Almost all of them wept as they filed down the corridor like pilgrims fulfilling some long-neglected obligation."

One of the veterans explained to me why it was so important: "You would have to be part of a combat infantry unit to appreciate what moments of relief Bill gave us. You had to be reading a soaking wet Stars and Stripes in a water-filled foxhole and then see one of his cartoons."

"Th' hell this ain't th' most important hole in the world. I'm in it."

Mauldin is buried in Arlington National Cemetery . Last month, the kid cartoonist made it onto a first-class postage stamp. It's an honor that most generals and admirals never receive.

What Mauldin would have loved most, I believe, is the sight of the two guys who keep him company on that stamp.

Take a look at it.

There's Willie. There's Joe.

And there, to the side, drawing them and smiling that shy, quietly observant smile, is Mauldin himself. With his buddies, right where he belongs. Forever.

What a story, and a fitting tribute to a man and to a time that few of us can still remember. But I say to you youngsters, you must most seriously learn of, and remember with respect, the sufferings and sacrifices of your fathers, grandfathers and great grandfathers in times you cannot ever imagine today with all you have. But the only reason you are free to have it all is because of them.

I thought you would all enjoy reading and seeing this bit of American history!

Paul Schultz