HIGH ALTITUDE EJECTION

“Out of control, upside down, and spinning.”

Air Force Captain Jon T. Little, U-2R Pilot

By

Ross W. Simpson

Two weeks before North Vietnamese tanks

and troops stormed into Saigon on April 30, 1975 and toppled the U.S. backed

government, a couple of highly-decorated veterans of the conflict in Southeast

Asia were ferrying two U-2R spy planes from Utapao Royal Air Base in Thailand back

to their home base at Davis-Monthan in Tucson, Arizona.

Captain Jon T. Little, known as “Jack” to

his friends, had directed air strikes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and in South

Vietnam almost a decade earlier as a Forward Air Controller [FAC] with the 23rd

Tactical Air Support Squadron based at Nahkon Phanom Royal Air Base in

Thailand. His wingman in the early morning hours of April 16th was Captain

Jim Barrilleaux, who flew 120 F-4 Phantom combat missions from Udorn, another

base in

Capt. Little and Capt. Barrilleaux had just climbed to altitude above 65,000 feet

and settled back in their ejection seats for an eight hour flight to

Captain Warren Pierce, another U-2

pilot, says three of the reconnaissance aircraft had been flown to

“We had been given a heads-up that

someone might be popping one off,” said Pierce, a retired Lieutenant Colonel

who lives in

“Snake,” as Pierce was known in the

squadron, was the “

Pierce says U-2 pilots were known by

their nicknames back then, not like today when Air Force pilots are known by

their call-signs. Little was called “Little Jon,” because another pilot named

John Sanders was much

taller than Little and was therefore called “Tall John.”

Barrilleaux was known as “Captain

HEADING HOME

Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Sinclair, who

flew U-2s for ten years and later became the squadron commander, was the

enroute team commander, the officer who escorted the aircraft to

As they leveled off above 65,000 feet, their

cruising altitude, “Little Jon” and “Captain

The only sound Little and Barrilleaux could hear in the headsets of their space

helmets was an occasional radio transmission as the tanker checked in with

Colonel Roger Cooper, the squadron commander in the command post at Utapao, as they

sped across the night sky at about 470 miles per hour.

Outside the cockpit it was 90-degees below

zero, but inside their pressurized space suits, they were toasty warm. Far

below through the clouds was the

What started out an hour and a half

earlier as a routine flight suddenly turned into a nightmare.

Without warning, the control column in

Capt. Little’s plane slammed forward against the instrument panel, causing the

aircraft to “porpoise,” go up and down.

“Little Jon” disengaged the auto-pilot,

eased back on the throttles and tried to pull the control column back, but it

wouldn’t budge. The U-2 pitched over nose first and spun out of control.

“Captain

“Out of control, upside down, and

spinning,” radioed Little as the violent maneuver

ripped off the tail of his U-2.

“That’s all I heard,” said Barrilleaux who

immediately contacted the tanker. Sinclair who had just dozed off was awakened

by a crewmember who said, “Little Jon’s punched out.”

Sinclair

didn’t know it at the time, but on the way out of the aircraft, something hit Little in the forehead, cracking the face shield on his

helmet, and knocking him unconscious. Barrilleaux thinks it must have been one

of two oxygen hoses that are designed to pop out of the plane’s internal oxygen supply on

ejection. The hoses have metal connections on the end,

but aren’t tied down to the pressure suit. During

ejection, they crack like whips.

Capt. Little fell more than 50,000 feet

at a speed of 614 miles per hour, the same velocity Captain Joseph W. Kittinger

Jr. experienced long before astronaut Neil Armstrong took “One Giant Step for

Mankind” on the moon. Kittinger stepped over the side of a balloon launched

from Holloman AFB,

Like Kittinger, Little’s fall lasted

more than three minutes before his parachute automatically deployed at 15,000

feet and carried his limp body to a soft water landing in the

During an interview in 1986 with Airman

Magazine at Patrick AFB, Florida where then Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Little

was deputy base commander, the West Pointer [Class of 1964] said the last thing

he remembered was the guy in the tanker telling him to “Get Out.”

“I pulled the eject handle, and the next

thing I remember I was in the water,” said Little.

Capt. Kittinger

may hold the world record for highest bailout and longest free fall in a test

flight, but Capt.

Little claimed the highest non-test flight bailout in the Air Force and the

longest free fall. A claim no one disputes.

The tanker was about 100 miles from

where the U-2’s autopilot malfunctioned and put the plane into a violent,

inverted spin. Just before he ejected, Little told

Airman Magazine “the extreme pressure resulting from the spin cracked the plane

in two.” The U-2 is designed to take a maximum

of 2.5Gs, Anything beyond that, and the aircraft comes

apart like a cheap tailored suit airmen had made during their tours in

The tail section of Little’s U-2 was found

later, but nothing else was ever located. Little’s son, Dax, has a piece of

Tail No. 68-10334, the 56th of 99 U-2s built by Lockheed Aircraft

Corporation.

A check of U-2 family serial numbers shows

Little’s aircraft was lost near Taiwain on

UNDER GOOD CANOPY

A radio signal in Capt. Little’s survival kit was picked up by the tanker after

ejection, telling those listening that he had managed to eject and was under a

good parachute. But the signal that can lead rescue planes to the spot where

the pilot is located apparently stopped when he hit the water. Nothing but

static was heard aboard the tanker.

It’s a good thing “Little Jon” was wearing

a self-inflating life preserver. Only U-2 pilots and Naval

aviators had them at the time. Without it, Little may

have drowned that night before he regained consciousness.

Downed pilots are taught to climb into their

self-inflating life rafts on their bellies, but Little

feared the oxygen connections on the front of his pressure suit would puncture

the raft and leave him bobbing up and down in shark-infested waters, so he

eased into the raft on his back. He noticed his emergency oxygen bottle was

empty, but couldn’t remember activating it.

“Perhaps I did it in a semi-conscious

state,” he said, “Or maybe I was conscious and just blacked it all out.”

If you have to fall more than 50,000

feet, maybe the best way is to be unconscious. Little said if he had been

conscious, he might have done something stupid, like mess with straps and try to get out of his ejection seat. It was totally dark

when he ejected; no moon and no stars, and if he had been conscious, he could

have become disoriented on the way down.

After “Little Jon” punched out, “Captain

While Cooper set in motion a

SAR [Search and Rescue] mission, Sinclair and Barrilleaux set up a search

pattern.

NOTIFYING NEXT OF KIN

Jane Little was taking a shower at their

home in Tuscon, oblivious to what had happened to her husband on the other side

of the world, when their six year old daughter came running into the bathroom out

of breath, and said, “Mommy, there’s a whole bunch of people in uniforms at our

front door.”

“Any pilot’s wife will tell you those are

words they never want to hear,” said Jane as explained to this reporter how the

squadron commander, his wife, a good friend, his wife and the base chaplain

only come to your door when something bad has happened, “and those are words

that will make your heart skip a beat,” Little said.

Wrapping

a towel turban-style around her wet head, and throwing on what he called an “old

crummy white robe that no one’s supposed to see,” Jane Little

walked slowly to the front door.

“I can’t say that I thought he was dead,

but all those things were running through my head as I opened the door,” said Little.

“Why are you here?” asked Little as she invited the officers in their dress blues to

come in.

When she asked what’s wrong with Jack, the

squadron commander told her he had to bail out of his plane a few hours ago.

“Is

he dead?” asked Little.

“No, but he’s missing,” said the Colonel.

Jane

didn’t want to frighten her daughter, Jenifer, who was standing beside her, so

she made up a quick story about her father jumping out of his airplane into the

water.

“Isn’t he silly?” asked Jane, “He could

have gone right next door and jumped into the swmming pool.”

Jane encouraged her daughter to go next

door and tell their neighbors what her daddy had done.

After an hour or so of idle chit-chat with

the officers and their wives who came to Jane Little’s house, the telephone

rang. It was the squadron calling to say that her husband had been located on a

fishing trawler.

Capt. Little was picked up by fishermen

about 30 miles east of Pattani, a village just north of the Malaysian border

after drifting in the Gulf of Siam about 350 miles south of Bangkok for seven

to eight hours.

While Little can’t

remember anything about his free fall, he could remember details of his rescue

by three fishermen, father, son and grandfather from one family. When they

lifted Little aboard their tiny boat, his survival radio

began beeping again.

It wasn’t long before Little

saw the tanker coming low over the water right at him. As it passed over the

trawler, he gave the tanker crew a “Thumbs Up,” and the pilot dipped his wings,

a signal that the crew had seen him and could now give Little’s location to

Col. Cooper back at the command post in Utapao. The crew also saw the orange

parachute that Little had tied to the stern of the

trawler as a signal for any plane that might be looking for him,

Normally, a pilot who goes down at sea, is taught in survival school to cut the parachute free,

because it could drag them under. But

“Jack the FAC” learned long ago in the skies over the Ho Chi Minh Trail to

think outside the box, before that term became popular. He knew the parachute

was bigger than anything else he carried in his survival kit, and it could be

seen for miles from the air.

Once Little

arrived at the fishing village on the

Little was a laid back kind of guy. So it

wasn’t surprising that the only reference to his hairy ejection from a

high-flying U-2 in a tiny notebook he carried in his flight suit read, “0340,

bailed out of my aircraft.”

Later that afternoon, two rescue

helicopters arrived at Pattani. Air Force PJs, Pararescumen, carried his life

raft, parachute and cracked helmet to one of the waiting CH-53s which took

“Little Jon” back to his old base at Nakhon Phanom where he caught a C-130 for

the flight to Utapao where “Captain America,” “Snake,” Col. Cooper and other

members of the 349th gave him a “Hero’s Welcome” as stepped off a

C-130, barefooted and wearing a borrowed flight suit. Cooper gave Little a bottle of champagne in

a plain brown paper bag, but he missed out on the “Little-Jon-Is-Alive-Party”

at the Officer’s Club. Little was hospitalized with a nasty bruise on his

forehead that blackened both of his eyes.

“We called him Vampire Man,” laughed Barrilleaux

who retired from the Air Force as a Colonel, and spent 18 years flying ER-2s,

NASA’s civilian version of the U-2R. ER stands for “Earth Resource.”

Barrilleaux has since retired as assistant chief pilot for ER-2s at NASA’s

Dryden Flight

Although Capt. Little missed tying one on

in Thailand, and planned to throw the First Annual “Little-Jon-Is-Alive Party” once

he returned to the states. the time was never right.

However, he and his wife celebrated the 10th anniversary of his

rescue a year before he died of cancer. They dined on what else; Oriental food.

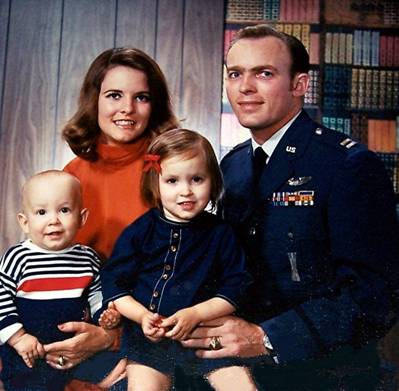

John Thomas Little met Jane Sawyer while

in pilot training after graduating from the

After Lt. Little returned from

From

“There are current manning requirements for

highly motivated, mature and experienced pilots for entry into the U-2 program.

Specific requirements are for Captains with about 2,000 hours flying time

(1,000 hours jet experience, center-line thrust or high performance time

desired) and diversification in at least two aircraft since UPT. Physical

requirements are a maximum sitting height of 36 ½ inches, a maximum

knee-buttock length of 25 ½ inches and no altitude impairments in your medical

history,” read the ad.

At 5 foot 9 inches tall, and a trim 160

pounds, Little met all of the requirements and was

accepted into the U-2 program, however the incident over the

His wife remembers the day her husband

was called to his squadron commander’s office and told that he was being

transferred out of the U-2 community to the

“I got screwed,” Little told his wife

before bed, “but the problem was the plane, not the pilot.” He never

complained, he just saluted and moved on.

“Unfortunately

for Little, pilots involved in air crashes are guilty

until proven innocent,” said Sinclair, who retired as a bird Colonel.

“Yeah,” said

Barrilleaux, “Even if the wings falls off, the pilot is blamed.”

Another U-2 crashed a month later in West

Germany; similar problem with the auto-pilot, but the Air Force apparently

needed to blame somebody for something and Jon T. Little became the sacrificial

lamb on the AF altar.

There was a hint of pilot error from the

get-go. SOF has learned that some high-ranking officers who conducted the

official investigation didn’t think Capt. Little “managed the problem properly,”

but those who knew him and flew with him said he did everything “humanely

possible” to save his aircraft that fateful night.

“But the aircraft can be squirrely,” said

Barrilleaux who told SOF that there is only ten knots or so between stall and “Maching Up,” the speed for level controlled flight.

“When that aircraft pitched over and

began to spin out of control, Little was doomed,” said

Sinclair who still doesn’t know how Little who served as his deputy at Patrick

managed to eject.

Sinclair says there was an unwritten rule

in the Air Force in the mid-70s. “Crash a U-2 and you never fly again.” But

that rule was broken at least twice. Col. Cooper crash-landed a U-2 on a frozen

lake in

Jack Little was a

track star in high school and at

THE FINAL RACE

Although LtCol Little was taking 30 chemo pills a day for cancer of the

adrenal glands, he somehow found the strength to run one more race before he

died.

Little won five gold medals in the “Over 40”

race in

Little didn’t live long enough to see his

daughter and son get married, or long enough to see

four grandchildren born. One of them is named Ian Tevis Dinwiddie. Ian Tevis is

Gaelic for Jon Thomas.

His

son, Dax, painted his dad’s trunk from

In keeping with his last wishes, Lt Col

Jon T. Little was buried in the

Jack was dressed appropriately in his orange

flight suit, ready for his next assignment.

His widow tried, but could not arrange a

flyover of military aircraft for her husband who had more rows of ribbons on

his chest than four-star generals, a Distinguished Flying Cross, 16 Air Medals

and the Air Force Commendations Medal among them. However, just as the chaplain

was about to offer words of comfort at graveside, Jane Little heard a “putt,

putt kind of sound,” and looked up to see a single engine Cessna like the Bird

Dog her husband flew over “The Trail” coming over the cemetery.

“I thought, you little bugger, you

arranged your own flyover,” said Jane.

Jack’s roommate in their junion and senior year at

William Murphy, a retired Air Force

Colonel, wrote,

“He was a pilot to the end and is now soaring in Heaven.” Amen.

Trophy Point at