A Vignette

by David R. Hughes

I have been asked by the team preparing

my nomination to tell this story.

More than a decade ago, I met Noel Dunne.

He was an Irish former Catholic priest who had worked for many years  as

a missionary among the Indians of Peru and Chile. There he learned

Spanish and helped these Indians create economic cooperatives to sell their

pottery. He then married and came to Denver, where, because of his

commitment to the poor and his mastery of Spanish, he was recruited by

the Christian Community Services to work in Alamosa, the central town of

30 very small towns, in Colorado's San Luis Valley. as

a missionary among the Indians of Peru and Chile. There he learned

Spanish and helped these Indians create economic cooperatives to sell their

pottery. He then married and came to Denver, where, because of his

commitment to the poor and his mastery of Spanish, he was recruited by

the Christian Community Services to work in Alamosa, the central town of

30 very small towns, in Colorado's San Luis Valley.

Several years earlier I had been doing

pro-bono work in the San Luis Valley from time to time, using advanced

techniques to connect up at the lowest possible cost, some very poor school

districts there to the Internet. Noel Dunne heard about that and

looked me up. He had an idea that somehow, some way, computer communications

could help support the work of CCS helping the poor in the most rural of

areas of the valley.

The San Luis Valley is 100 miles long,

50 wide, surrounded by the 14,000 foot Sangre de Cristo and Rio Grande

mountain ranges, a giant flat ancient lake bed with the head waters of

the Rio Grande River running through it en route 1,500 miles to the Gulf

of Mexico. It has been homesteaded since the 1600s by migrating Spanish,

then Spanish-Americans, then Hispanics.

This magical valley is home to some 35,000

rural folk in 30 small agricultural communities in 16 separate small school

districts. An often desperately poor, devout, people, isolated from

even the most rural Catholic churches and ordained priests, they had rich

inner lives, vivid art, an ancient religion-centered culture, beautiful

churches -- all against the backdrop of some of the most magnificent mountain

peaks in the nation. With 80% Spanish speaking and 20% Anglo in the

southern end of the valley and the reverse in the north, they were a cultural,

political, economic, educational, and technological challenge.

Earlier I had successfully linked some

schools to the Internet through Adams State College servers. And

at one of the poorest schools in central Colorado I had hooked up the first

wireless devices (using some modems never built for what I used them for)

between a classroom and a server in the building. (Somehow, this

had caught the attention of Tom Kalil, Vice President Gore's technical

advisor, who then told the FCC they needed to talk to me).

So Noel Dunne asked me to work with him

to create computer bulletin-board technology that these valley people --

immigrant families, white farmer-exploited migrant workers, the simply

poor -- could use to communicate with each other. I helped him create

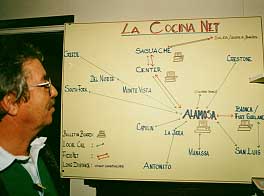

a dial-up modem, local network called "La Cocina" -- the Kitchen, where

in Hispanic  homes

the important conversations take place. La Cocina's bulletin board

informed these people about housing, the education of their children, and

legal representation. It went on to provide (Noel Dunne's own specialty)

self help for very small businesses and income producing activities, and

the web based marketing of some of their products, like weaving.

Cooperative marketing allowed them to get better prices for their handicrafts. homes

the important conversations take place. La Cocina's bulletin board

informed these people about housing, the education of their children, and

legal representation. It went on to provide (Noel Dunne's own specialty)

self help for very small businesses and income producing activities, and

the web based marketing of some of their products, like weaving.

Cooperative marketing allowed them to get better prices for their handicrafts.

I then got Noel Dunne together with an

interesting woman dedicated to online education, Carmen Gonzales, and another

incredible man -- a Professor Tomas Atencio then at New Mexico University

who had a brilliant thesis called "Resolana." Resolana was

the ancient Hispanic "way of knowing" in which the men of the tiny towns

towns sat on the sunny side of the plaza and, through oral dialogue, formed

and perpetuated the values, knowledge, and wisdom of the village (unlike

the European/North American "way of knowing" through academic study, science,

and printing). Professor Atencio believed that unless traditional

Hispanics, such as those in Northern New Mexico, learned the new technologies

and used modern communications to replicate this way of knowing, they would

simply become the information-sweatshop workers of the 21st Century and

lose their ancient culture while gaining the middle class -- a prospect

that bothers Hispanics profoundly.

So, when Professor Atencio saw that I had

created an all-purpose computer language with which people could communicate

both linguistically and artistically (so that symbols could be sent back

and forth, but that's another story), he said this was the technology he

had been looking for for years. We formed a movement called "Resolana

Electronica." It flourished for a few years until the rise of the

Norte Americana World Wide Web brought the crass values of American TV

and print magazines to the Internet, and lured the Hispanic children away

from their gentle but profound "la familia" and resolana-centered community

roots.

Ironically it had been at Center, Colorado,

many years before, where the Anglo-Hispanic split was extreme, that as

Chief of Staff of Fort Carson I had for General Rogers, authorized an outreach

of civic action that gave the Hispanics who lived "south of the ditch"

in town their first septic systems and clean water pipes. We required

the  white-dominated

town government to come to consensus with the Hispanics on projects to

be done through public meetings, or we would not aid the town. In

1985 I was told by a grateful Hispanic liquor store owner, who had been

a lieutenant at Carson back then, that this had permanently changed the

political power structure in Center. Hispanics got on the school

board, into town and country politics and government, and things balanced

out better after we, the Army, left. (I had utterly forgotten that

episode. It was only after my coming to town and the school with

a pair of radios that the man who read about that asked that the school

call him when I was next in town so he could meet with me. It was

a touching meeting for him to be thanking me before the Superintendent

and staff of the Center School District for those actions so long before) white-dominated

town government to come to consensus with the Hispanics on projects to

be done through public meetings, or we would not aid the town. In

1985 I was told by a grateful Hispanic liquor store owner, who had been

a lieutenant at Carson back then, that this had permanently changed the

political power structure in Center. Hispanics got on the school

board, into town and country politics and government, and things balanced

out better after we, the Army, left. (I had utterly forgotten that

episode. It was only after my coming to town and the school with

a pair of radios that the man who read about that asked that the school

call him when I was next in town so he could meet with me. It was

a touching meeting for him to be thanking me before the Superintendent

and staff of the Center School District for those actions so long before)

I donated $10,000 -- $5,000 to help La

Cocina get started, then later $5,000 to Tomas Atencio to help get La Resolana

Electronica get going. The latter was a community communications

server housed at the University of New Mexico which was linked to small

systems and modems in small Hispanic communities and Indian pueblos in

Northern New Mexico. They couldn't afford it themselves.

I offer this vignette to provide up close

and personal evidence of my sometimes successful (sometimes not) efforts

to assist the poorest, and most rural, and minority-culture areas of the

country with grass roots telecommunications. In this case it was

the very depressed San Luis Valley, with two of the lowest per capita income

counties in the nation.

Dave Hughes

|